[The general membership of the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) is currently voting on a bylaw amendment to strike the word "non-political" from its self-description and add a clause reaffirming the organization`s committment to functioing as a 501(c)3 non-profit entity. The amendment was first introduced at the 2016 Annual Meeting, during which the Business Meeting voted 247-57 in favor of putting it up to a general membership vote. More than eleven former MESA presidents came out in support of the amendment in a joint letter. In the following roundtable, longtime MESA members Elyse Semerdjian, John Chalcroft, and Asli Bali share their thoughts on MESA as an academic institution, their roles within it, and why they each support the bylaw amendment. The text of the amendment and instructions on how to vote follow follow the roundtable responses. This roundtable was organized by several individuals who participated in authoring and introducing the bylaw amendment. They have submitted it to Jadaliyya for publication and welcome its republication (without modifcation) elsewhere.]

Organizers: How long have you been a MESA member, and what roles have you taken up in the organization? What is your favorite thing about MESA?

Elyse Semerdjian: I have been a member of MESA since 1996, and have served on its Nominating Committee. I am currently on the editorial board of IJMES. I love MESA because it is my intellectual home, a place where I find community during the annual meetings since I work in a remote part of the country the rest of the year. It’s the time of the year that I get to engage with colleagues in Middle East studies. I even dance with them, thanks to those fabulous DJ Bassam parties, which is both awkward—because academics aren’t exactly known for their dancing abilities—and exhilarating.

John Chalcraft: I have been a member of MESA for most of the time since the early 1990s. I have attended the majority of annual meetings since then—organizing panels and presenting papers. MESA has played an important role in my own scholarly formation, and I feel like I owe it a debt of gratitude and loyalty. It is an important association because it broke with Orientalism and narrow security agendas long ago. MESA has done much in recent decades to foster critical, interdisciplinary, and exciting scholarship, while providing an array of services to help build a cosmopolitan and convivial community in Middle East studies.

Asli Bali: I have been a MESA member on and off since 2004. During my time as a member I have served on the Board of Directors, the Program Committee, the Committee on Academic Freedom (CAF), and, most recently, the Task Force on Civil and Human Rights. My favorite thing about MESA is that it provides a scholarly home that is both interdisciplinary and truly international—with significant numbers of participants in the annual meeting traveling from the Middle East to give presentations and contribute perspectives that enrich the conversations at the meeting and foster transnational collaboration.

Organizers: How do you think this bylaw amendment would strengthen MESA as an academic association?

Elyse Semerdjian: Perhaps MESA after 11 September 2001 is a different organization that it was before. While Middle East scholars were certainly under attack before then, we did not have watchdog groups like Campus Watch smearing academics on the internet for being critical of the US War on Terror, critical of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, or doing their job by offering a scholarly view of Islam within an environment of vitriol and willful ignorance. Fifteen years on, these groups have multiplied and so have the attacks on scholars. If we think globally, the attacks on scholars have expanded to include the assassination of PhD student Giulio Regeni in Cairo, assassinations of Iraqi professors after the US occupation of Iraq (almost 300 since 2003), the imprisonment of Professor Homa Hoodfar in Iran, the detention of Sami Arian in the United States (acquitted, yet deported anyway), the bombing of universities in Gaza and Aleppo, and now the mass firings and arrests of our colleagues in Turkey over the last year. As scholars in a post-September 11 world, we spend a great deal of time thinking about and acting on issues of academic freedom, civil rights, and human rights in the United States and abroad. We do this as an extension of our academic work in order to protect our workspace by speaking out on behalf of vulnerable colleagues who live and work in conflict zones. This work, which has come natural to us as an organization, certainly cannot be construed as apolitical. However, this work is, and should be, advocacy work to protect academic freedom (in all its forms, including speech we find morally repugnant), because our colleagues look to us when they are wrongfully fired, imprisoned, attacked, and bombed.

John Chalcraft: This amendment will undoubtedly strengthen MESA. If we insist, for no particular reason, and under no meaningful compulsion, that we are “non-political,” we offer ammunition to those who would claim to dislike whatever politics they read into our association or the views of its members. Enemies of critical, controversial, or hard-hitting academic research will find it easier to attack us by stating that we have “become political” in violation of our own bylaws. Eliminating the phrase “non-political” from the bylaw is a costless and entirely sensible way to avoid this self-imposed trap. In the current climate in the United States, perhaps more than ever, such attacks would be launched by the powerful, the bullying, and the well-connected. They would be aimed at silencing critical, nuanced, and alternative forms of scholarship that speak truth to power, doing considerable damage to our field.

Asli Bali: Scholars from the Middle East and those who study the region have been under attack across a number of highly politicized contexts. In Turkey, academics face mass purges and the stifling of all forms of academic freedom under a state of emergency that treats dissent and critical thinking as a threat to national security. Elsewhere in the region, armed conflict and rubrics of counter-terrorism have provided pretexts to repress academic freedom and target individual scholars. Scholars studying the region in North America and Europe are frequently subjected to political campaigns by outside advocacy groups that target individuals and programs studying the Middle East—because their research touches on controversial topics. In addition, policy changes, like the recent Executive Order seeking to restrict travel from seven Middle Eastern countries to the United States adversely impact the field of Middle East studies. In all of these instances, MESA has been called on to raise its voice to advocate for academic freedom and to oppose policy changes that negatively affect our membership. These are appropriate activities for a scholarly association and they are also forms of political engagement that our bylaws should enable.

Organizers: What would you say to the undecided MESA member who has concerns that such a bylaw amendment would either radically transform the nature of the organization or open the door to such a transformation?

Elyse Semerdjian: I would share a personal story about why I am personally motivated to pass this bylaw amendment removing the “non-political” clause. As an Armenian, the mass arrest and execution of 250 Armenian intellectuals in Istanbul in April 1915 weighs heavily on my mind. Armenians commemorate the event every 24 April, when they visit the sites of the hangings in Pera, Taksim, and Haydarpasha. We do this to remind ourselves that historically, whether in Nazi Germany, Ottoman Turkey, or Pol Pot’s Cambodia, intellectuals are often on the front line of tyranny and their loss can devastate a nation. While we certainly do not live in an age that rises to this level of oppression, the Armenian muscle memory flexes for me when my colleagues are under attack.

I don’t believe that the bylaw will change what the organization is already doing. It will simply put our mission in line with the work we are already doing as post-September 11 academicians. In addition, I don’t think it will make MESA a political organization. It will merely remove the false advertising that we are “non-political” when sometimes, as in the case of colleagues whose rights to academic freedom and civil rights are under attack, our duty is to advocate for them. I would also ask my colleague to take a look at the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), an organization that took on new political value during McCarthyism when professors were subjected to red scare witch trials. The AAUP does not call itself non-political in its mission statement. Today, MESA increasingly has to take on a similar advocacy role offering legal advice and directives for Middle East scholars who may not get that advice from their institutions.

John Chalcraft: My view is that the amendment would not bring about any kind of radical change. A whole community of scholars is not given to such a thing, for better or for worse. In fact, the change would most likely allow MESA to be truer to itself. The number of scholars among us who believe in an objective and universally correct way to distinguish the political from the non-political in matters of education, research, and public awareness/engagement is probably rather small. Most of us believe that these boundaries are very difficult to set in stone. Indeed, many of us suspect that those who police these boundaries do not do so on the basis of objective criteria, but are most likely pursuing an unnecessary political exercise of their own. MESA does not pass judgment on what is political or non-political, as to do so is to invite needless controversy. My sense is that this is a fairly common sense view, and acting on it will not suddenly change MESA. It will merely confirm a widely held position within it. It is my understanding that the ‘non-political’ clause was introduced originally to combat needless and counter-productive division and polarization within the Association. It would seem to me that the same very same logics now mandate its removal.

Organizers: MESA’s board has recently established a Task Force on Civil and Human Rights and issued a statement regarding the Executive Order effectively amounting to a “Muslim Ban.” In light of these organizational and political developments, how do you think this bylaw amendment strengthens MESA?

Elyse Semerdjian: MESA’s statement on the “Muslim Ban” is an example of a circumstance in which our association, for the protection of its members, must take a stand against blatant civil rights violations that have become normative since 11 September 2001. We must recognize that MESA for so many of us is a lifeline. MESA is the place we go to for guidance since our neoliberal academic institutions have become more cautious, and—like any good corporation—they are often more focused on public image, financial stability, and risk aversion rather than the rights and wellbeing of their faculty, staff, and students. Perhaps this is why academic freedom as a founding principle has been less of a priority for college and university presidents in recent years. In this environment, academics will be looking for guidance from their professional associations who will have to advocate for them when their institutions fail to do so. That is why I, for one, and thankful to have MESA to lean on.

John Chalcraft: MESA must engage in public with issues that touch on its vital, constituting purposes. This is right and proper for any cultural, scientific, or educational association that does not let down its membership and abrogate its responsibilities. However, there are those who will claim that this Task Force is “political,” and use this as a stick to beat us, especially given the way our bylaws are constituted. This case therefore illustrates nicely the trap that the ‘non-political’ stipulation in the bylaws creates for us. Happily, we can avoid the trap by eliminating these words from the bylaws.

Asli Bali: I applaud MESA’s decision to create a Task Force on Civil and Human Rights in these turbulent times. I also strongly supported the statement that was issued concerning the Executive Order. I believe the bylaw amendment will place our Association on firmer ground in engaging with policy issues that directly impact the field of Middle East studies and our membership. Such engagement is both necessary and appropriate for MESA to undertake and will be facilitated by the bylaw amendment.

How to Vote [Vote "Yes"]

The general membership is currently voting on the amendment during the period between 1 February 2017 and through 15 March 2017. Only current MESA members (meaning individuals with a 2017 membership can vote in the election.]

- To read the proposed amendment, click here. [Vote "Yes"]

- If you are a current MESA member and would like to vote in this election, click here. [Vote "Yes"]

- If you are a past member and would like to renew your member, log into MyMESA and renew your membership for 2017, and then proceed to the link for the ballot. [Vote "Yes"]

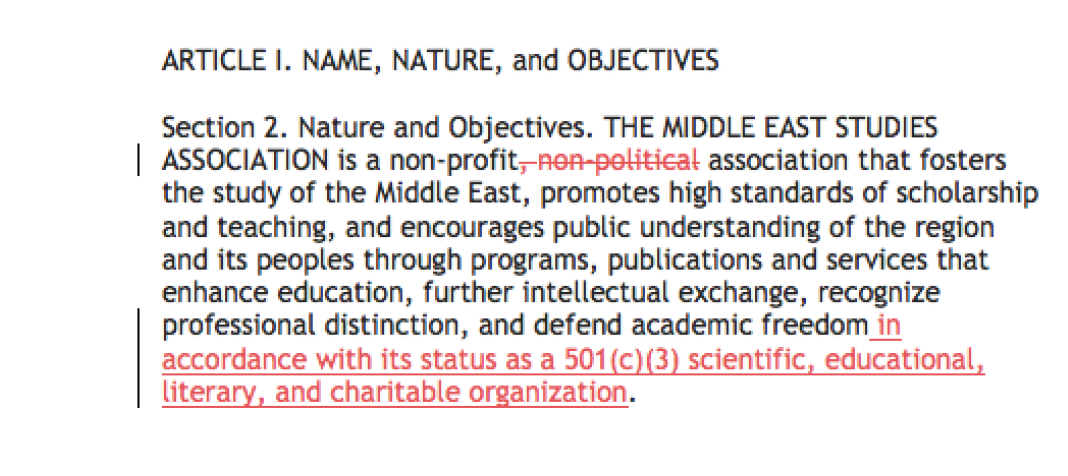

Track-Changes Display of Proposed MESA Bylaw Amendment